When people think of serious crashes they tend to think of things like drunk drivers, extreme speeds and people acting recklessly.

But a new study from the AA Research Foundation challenges these perceptions and found many crashes involve everyday people not doing anything extreme.

The first-of-its-kind study found that in around three quarters of crashes where vehicle occupants were seriously injured the drivers were generally following the rules of the road, but they made a mistake or a poor decision, or something unexpected happened. To put it another way, they were going about their ordinary business when something went wrong and they were seriously injured.

The focus in road safety is generally on the more than 300 fatal crashes that happen each year but there are about 10 people seriously injured from road crashes for each death and the social cost to the country is estimated at $776,000 per reported serious injury. This was one of the reasons the AA Research Foundation wanted to improve our understanding of serious crashes and, in particular, what proportion of crashes resulted from extreme behaviours and what proportion were the result of what the research called system failures.

Hamish Mackie of Mackie Research explains: “We took the detailed reports from 300 passenger vehicle crashes that resulted in either a fatality or a serious injury, and we analysed them in terms of the “safe system” that underpins the Government’s current road safety strategy. We looked at whether there had been driver error, or whether speed was an issue. Was the vehicle safe? Was the road unsafe for some reason? And we set some criteria that triggered a “reckless behaviour” categorisation, like driving drunk or without a licence, driving at more than 20km/h over the speed limit, or not wearing a seatbelt.”

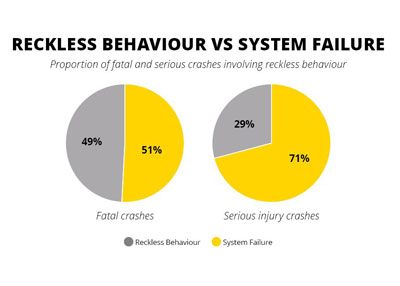

As can be seen below, the research found significant differences between fatal and serious injury crashes.

For fatal injury crashes there’s an even split between reckless behaviour and system failures. But when it comes to serious injury crashes, there are many more crashes where a system failure was identified. This suggests that we can significantly reduce the serious injuries on our roads by not just trying to stop extreme behaviour but also looking to improve the whole ‘safe system’.

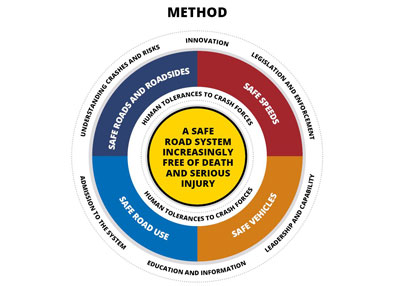

The concept behind the safe system (shown in the diagram below) is that the harm from crashes comes from the combination of four different ‘pillars’: the road users, the speeds they are travelling, the vehicles they are in and the roads they are on.

Another key finding of the research was that the majority of crashes, both fatal and serious, involved failings across three or four pillars of the safe system. An error by the road user was involved in over 90% of both fatal and serious injury crashes (we are, after all, human and we all make mistakes) but in most cases people were also in vehicles that were less than ideal in terms of safety, and on roads that could be made more protecting or with speed limits that may not match the environment.

One particularly interesting set of findings from the research relates to the safe vehicle pillar. In almost 80% of fatal and serious crashes in the research, the safe vehicle pillar was triggered.

The research clearly showed that if two cars collide, occupants in younger cars and ones with more safety features suffered less harm than those in older cars. Cars older than 14 years were less protective than those that were under 14 years in age. These cars don’t tend to have ESC (Electronic Stability Control) and while they may have a driver airbag, they may not have passenger and side curtain airbags. This is a particular challenge in New Zealand where the average age of vehicles in our fleet is more than 14 years old (compared to Australia’s 10 and Japan’s 8)

The research also showed when looking at the different sorts of passenger vehicles on the road, SUVs, vans, 4WDs and utes had a higher risk of rolling-over in crashes.

So what can we take out of the research? From the AA’s perspective, it highlights that for us to improve road safety we need to be doing more than just targeting the behaviour of road users and extreme actions. If a crash happens on a road with barriers on it there is less chance that it will result in serious injuries or deaths. Getting more people into more modern vehicles with side-curtain airbags and electronic stability control will also mean less severe consequences if they are involved in a crash.

And as individuals we can all do things to minimise our risks of being seriously hurt on the roads like not driving when we’re tired, avoiding distractions behind the wheel, making sure everyone wears a seatbelt and looking for a 4 or 5 star safety rated car the next time you are looking to buy.

By doing so you’ll be lowering the risks of a serious injury for you and your loved ones because at one point or another, we all make mistakes.

Accident analysis

The study differentiates between deliberate ‘reckless behaviour’ causing an accident, and ‘system failures’ which defines unintentional errors.

Examples of reckless behaviour:

• Having a blood-alcohol count over the licence condition (0 for youth, 0.08 for adults)

• Not having a current licence

• Driving 20 km/h over the posted speed limit

Examples of system failures:

• A vehicle not having front or side airbags

• Hitting a roadside pillar

• Driver crossing a centre line

Reported by Simon Douglas for our AA Directions Autumn 2018 issue